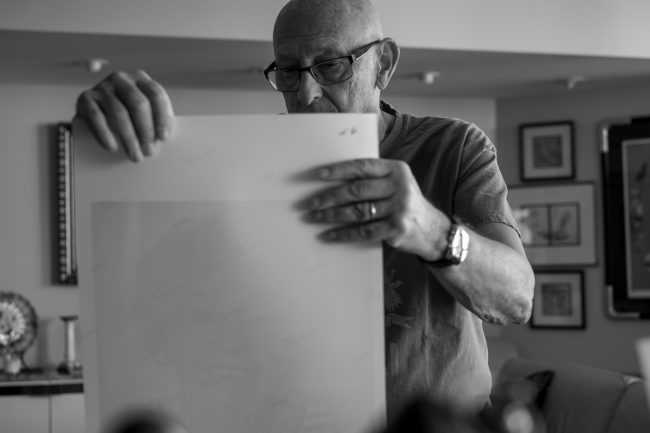

Every portrait is taken in extreme close-up without being retouched. The lighting is harsh and the emotion is raw. The pain is tangible. “I want to see every wrinkle, every defect in their faces because it is part of their characters,” said Laszlo Selly, the 83-year-old Holocaust survivor and photographer behind this project. “It’s part of who they are.”

The memories he and other survivors have of their pasts are his reason for starting this new project. He wants people to remember a brutal time in our history so that it will never repeat.

“I want them to be able to look into their eyes and imagine the memories these people have,” Selly said.

Laszlo Selly was only a kid when his home country, Hungary, was occupied by the Nazis. His life was turned upside down in just a couple of seconds and remained that way for several years before the country was liberated by the Soviets.

“Before, life was nice,” Selly said. “I was a little kid, four or five years old, and life was easy. My brother and me, we had no worries. We did what little kids do at that age.”

His family was fortunate enough to have never stepped foot in a concentration camp. They survived that time in Budapest’s Jewish housing. But their lives secluded from the rest of the country weren’t much better than others in places like the Polish camps.

Freedom was a distant memory. Their new reality was living crammed up in an apartment shared with three other families, where food was a luxury and so was your next breath.

“It never became normal, things happened so fast and fear took over,” Selly said. “We realized at a very young age that people wanted to hurt us.”

Every morning there was a new group of people lined up and executed in front of the entire neighborhood. And every morning Selly and his family prayed they wouldn’t be next.

One night there was a knock on the door. When they answered, their hearts dropped. A Nazi soldier ordered them to be lined up outside by sunrise. They knew what that meant for their fate. The families spent the night hugging and praying that morning wouldn’t come.

Just before sunrise, there was a loud banging at the door. All the families in the apartment gathered somberly but were shocked when the soldier on the other side was not a Nazi. They were informed that they had been liberated. There was shock, joy and relief running through their minds. It was over — almost.

After the war, Selly’s father changed the family’s last name from Swartz to Selly to protect them from discrimination because anti-Semitism was still very prominent. “Us children would be able to have an easier life, not having to deal with having a Jewish name,” Selly said.

In the years that followed, they were under Soviet rule. Although Selly was allowed to go back to school, he found it difficult to concentrate on his work.

Selly was never one for books, but always loved pictures and the art of photography. One day while rummaging through his parents’ closet, he found an old camera. He asked his father how to use it. “I don’t know,” the older Selly replied. So, young Laszlo decided to teach himself and began taking pictures of everything.

After learning how to work with the camera, he dove into the world of photography and learned everything there was to know about it.

“I was known as the guy with the camera,” Selly said. He continued to pursue the art and became an apprentice photographer at age 15.

When the Hungarian revolution erupted in 1956, Selly and his brother, Rudolph, fled Hungary. They were captured by the Austrian police and sent to a refugee camp. Red Cross officials contacted his uncle, who sponsored Laszlo and Rudolph to be brought to the United States.

They immigrated to New York, but no one wanted to hire a 17- year-old kid who couldn’t communicate well in English.

So Selly worked various part-time jobs involving photography and eventually opened his own commercial studio. His clientele included large food companies, advertising agencies and top magazines. In 1998 he retired and decided to travel and focus on fine arts photography.

Selly learned about Washington’s Holocaust Memorial Museum, which opened in 1993, through a friend and was asked if he would join a group of survivors to share their stories weekly.

He decided to volunteer to educate future generations about the Holocaust, and in 2019 was inspired by the experience to start a project of his own: The Holocaust Survivor Portraits.

He has successfully captured 32 survivors, but isn’t finished. Selly said he will continue to take photos of as many survivors as he can. (Only about 400,0000 of the millions who survived are still alive.) The idea is to eventually create an exhibition for people to come to see and hear their stories.

“They are being brutally honest,” Selly said. “You are able to feel their pain through the image.”

Selly is also a part of Names, Not Numbers, a program being hosted by the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Miami Beach that allows students the opportunity to learn firsthand about the Holocaust by helping make a documentary.

Students sit down with Holocaust survivors and hear their stories. Selly will be one of those featured. Recently, the production process was shown in the David Posnack Jewish Community Center Jewish Film Festival.

“These people will not be here any much longer,” Selly said. “Once they are gone, the holocaust deniers will come out and say it never happened.”