The COVID-19 pandemic changed routine life drastically in just a year. Job loss, isolation and fear have been just a handful of the side effects of a global pandemic. Mental health has also been on the decline in the United States in recent years. The stress of living through a pandemic’s isolation has taken a toll.

The Decline of Mental Health in America

According to a 2020 report from Mental Health America, the prevalence of mental illness has increased among adults in the past few years. Screenings of people with symptoms of depression and anxiety only grew throughout 2020. The number of those seeking help with anxiety and depression, according to screenings conducted by Mental Health America, increased by 93% for the first nine months of 2020.

COVID-19 and Mental Health

The Centers for Disease Control in collaboration with the National Center for Health Statistics started conducting a survey in April of 2020 to gauge the socioeconomic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Americans with a focus on mental health. Surveyed groups reported the frequency in which they experienced symptoms of depression and anxiety on a weekly basis.

With millions of cases reported, more than 500,000 deaths, and a demoralizing increase of variants spreading throughout the country, mental health has been an underlying concern. External stresses tend to trigger feelings that are symptomatic of anxiety and depression– and while this does not necessarily mean that someone has depression or anxiety, it could mean the two can develop or that they already exist in a mild form.

Depression, Anxiety, and Education

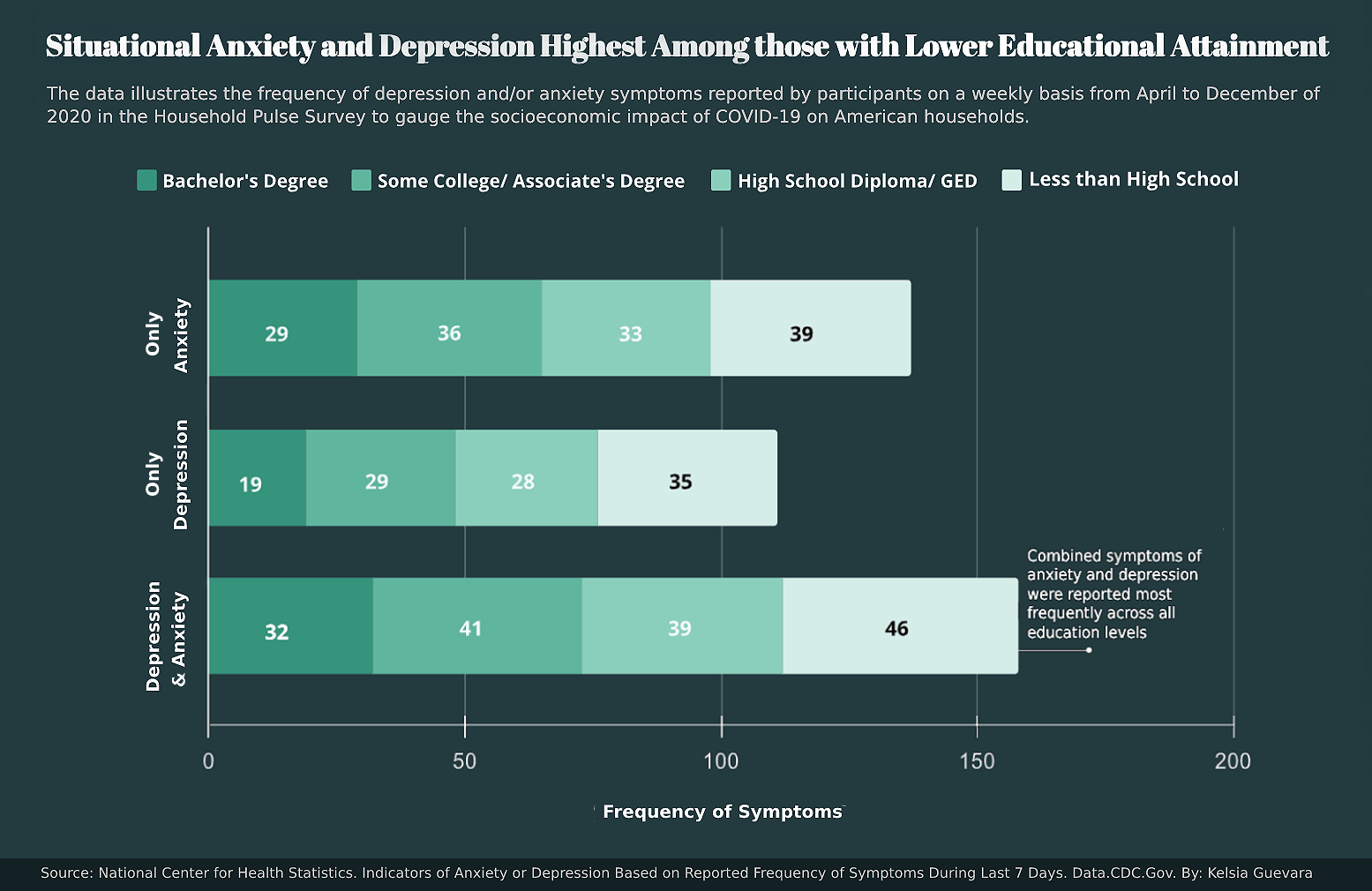

COVID-19 has made these two disorders prominent among people from all walks of life. However, adults with lower educational attainment are the most vulnerable to experiencing symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Combined symptoms of both anxiety and depression were significant in all surveyed groups but it was those with an education level below high school that were prone to experiencing both. Depression and anxiety independently were also highest in this same group. As the level of education decreased, the frequency of symptoms increased.

Those with bachelor’s degrees reported experiencing significantly less symptoms than every other group. The reported number of symptoms experienced on average increased by 84% from what the bachelor’s degree group reported to what the less-than-high-school group reported for combined symptoms of both. This pattern repeated with anxiety and depression symptoms being reported independently. The average frequency of reported symptoms increased by 34% and 84% for only anxiety and only depression, respectively.

Higher education tends to increase access to more and better resources including those that tackle mental health. This gap in accessibility could be a factor in the disparate number of symptoms experienced.

Younger Generations: The Vulnerable Group

While the symptoms of anxiety and depression were prevalent in those with lower educational attainment, the ages of those who are experiencing these symptoms also have their role to play.

Youth in the United States are experiencing mental illness at a higher rate than ever before. The percentage of youth experiencing major depression was 9.7% in 2020 versus the 9.2% in 2019 and almost 50% of them are not receiving the care they need according to Mental Health America.

Mental health conditions tend to develop in early adulthood and introducing outside influences like COVID-19 could further endanger an already vulnerable population.

The youngest age group, 18–29 year-olds, had the highest number of reported symptoms across the board. This group reported experiencing symptoms of anxiety an average of 44 times weekly over eight months. The second youngest surveyed population, the 30–39 year-olds, followed closely behind as they reported experiencing symptoms an average of 39 times during the same period. This was over twice as much as what was reported by both the 70–79 age group and the 80 and above group.

The contrast between those in their 30s and the eldest surveyed population, the 80 and above crowd, is drastic. The eldest reported less than half as many symptoms of both anxiety and depression than the youngest age group. The fear of COVID-19 related isolation seems to be more present in younger generations, and age could be a factor.

People who are struggling with the loneliness of isolation are screening as at-risk for mental health conditions. The pandemic’s contribution to anxiety and depression’s growth has ensured that these numbers are ever-growing and widespread. The United States has a high volume of people experiencing symptoms of both disorders but the pandemic offers a series of very particular stressors for people that make these symptoms more pervasive.

A Silent National Crisis

On a national scale, the United States is showing an increasing number of people experiencing mental health conditions. The number of those seeking help for anxiety and depression specifically has increased from 2019 to 2020. From January to September of 2020, 315,220 people were screened for anxiety and 534,784 people were screened for depression, more than the total number of screenings for each in 2019.

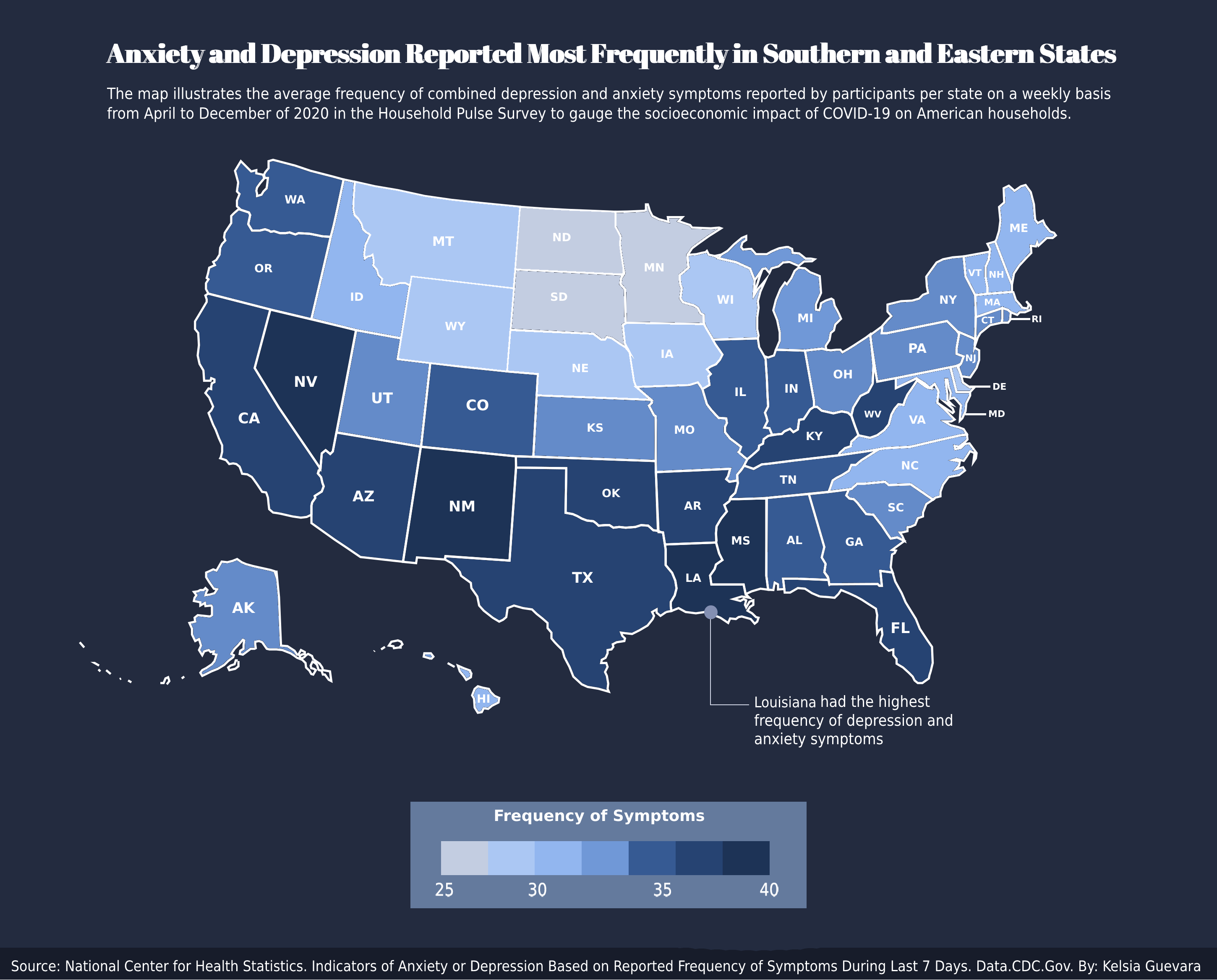

Only a handful of states had its residents reporting a lower number of symptoms. These states were North Dakota, South Dakota and Minnesota. The highest concentration of symptoms reported came from the Southern and Eastern parts of the country.

Population is also not the sole determinant of the high number of symptoms reported as California, Florida and Texas have lower symptoms reported than some less populated states — like Louisiana, which reported the highest rate of symptoms in all 50 states.

The reason for this could be demographic as some of these states have the highest minority populations in the country or based on how rural these states are. North and South Dakota are a few of the most rural states in the country and Minnesota is not far behind with a rural index of 139, an indicator of how much more rural the state is than the nation as a whole, according to non-profit corporation site National Popular Vote.

Lack of resources could be a factor in this contrast between reported frequencies. Both minority communities and rural populations have experienced a lack of access to mental health resources. Just six years ago, people that identified as white receiving mental health services was higher than those who identified as Asian, Black and Hispanic by 17% to 26% according to the American Psychiatric Association. These same populations also experience barriers to mental health resources despite being especially vulnerable. These barriers can take the form of stigma, cultural differences and distrust in the healthcare system.

For rural populations barriers to care also exist. Not only do rural populations also tend to have higher populations of indigenous people and people of color, but they also experience issues with accessibility in general.

Rural areas have a shortage of mental health care workers, according to the Rural Information Hub. Specialized care like psychological treatment is in short supply as 60% of mental healthcare visits are through a primary care provider instead of specialty care meaning that these populations may not be getting the exact treatment they need when they do see a doctor.

Coping with COVID-19

The pandemic has been a novel and uncertain event to live through, one whose consequences may not be known for some time. What is certain is that mental health is of increasing concern in the United States and factoring in how dramatic the pandemic has been on every facet of daily life, mental health should be that much more of a health concern. Since the April to December 2020 period that responses were collected in, COVID-19 deaths and cases have only increased. From just over 1 million cases and approximately 60,000 deaths in April 2020, there are now 30.2 million cases and over 500,000 deaths as of March of 2021.

All data came from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data was limited to the reported responses from April to December of 2020 | Download Dataset

Cited works:

Mental Health America. (2020) The state of mental health in America. Retrieved March 20, 2021, from https://www.mhanational.org/issues/state-mental-health-america

National Popular Vote. (2020, January 12). Rural states are almost entirely ignored under current state-by-state system. Retrieved March 23, 2021, from https://www.nationalpopularvote.com/rural-states-are-almost-entirely-ignored-under-current-state-state-system

The New York Times. (2020, March 03). Coronavirus in the U.s.: Latest map and case count. Retrieved March 19, 2021, from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-us-cases.html

Virginia CommonWealth University. (2014, April 29). Why education matters to health: Exploring the causes. Retrieved March 22, 2021, from https://societyhealth.vcu.edu/work/the-projects/why-education-matters-to-health-exploring-the-causes.html

Mental health disparities: Diverse populations. Retrieved March 24, 2021, from https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/cultural-competency/education/mental-health-facts.(PDF)

Noguchi, Y. (2020, July 04). Why some young people fear social isolation more than covid-19. Retrieved March 22, 2021, from https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/07/04/885546281/why-some-young-people-fear-social-isolation-more-than-covid-19