Thirty years after Hurricane Andrew plowed through Homestead, experts are still left with the fundamental problem of bracing for massive storms. Scientists, researchers and engineers at Florida International University ask how can we build stronger and better before the next Andrew Hits.

A Cautionary Tale

An octopus in the parking garage. It sounds like a juvenile story from a children’s picture- book about a sea creature coming to land, but the octopus in a parking garage was reality for Richard Colin in November 2016 when he found the floating cephalopod near his parked car at his luxury South Beach condominium. Washed up from a drain in the floor, the story of this octopus is stranger than fiction, but it should serve as a cautionary tale of a city that is increasingly vulnerable to a changing climate and rising seas.

1992 and a storm named Andrew

Twenty-four years prior, a different creature rose from the Atlantic to terrorize Miami-Dade County. On August 24, 1992, Hurricane Andrew struck near Homestead as a Category 5 storm with peak winds of 175 mph. It is the most destructive hurricane to ever hit Florida in terms of structures damaged or destroyed.

Only four Category 5 storms have hit the United States. And of those four, only one (narrowly) missed Florida, reinforcing what is already known: the overhanging peninsula that splits the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico is extremely vulnerable to intense tropical cyclones. Hurricane Michael was the most recent of these monstrous storms when it struck near Mexico Beach, FL in the fall of 2018.

Bracing for Wind

“Andrew changed everything,” says Erik Salna, an Associate Director for the International Hurricane Research Center (IHRC) at FIU. “It woke up Florida.”

In the wake of Hurricane Andrew, new building codes emerged as two grand juries found that homes hard-hit by Andrew were vulnerable because of poor design, shoddy construction and inadequate design. New building codes were established, particularly relating to wind-resistance; product approvals for the construction materials manufactured and installed in homes; and education and certification for inspectors, building officials and plans examiners.

“The state of Florida is number one in building codes. Number one in emergency management, number one in preparedness,” Salna says.

Testing of these building codes and infrastructures resiliency to wind happens at FIU. The Wall of Wind (WOW) is a 12-fan, 8,400 horsepower hurricane simulator that tests everything from roofing to traffic lights. The testing-facility is a post-Andrew product aiming for a more wind-resilient state.

Sea level and stakes are both rising

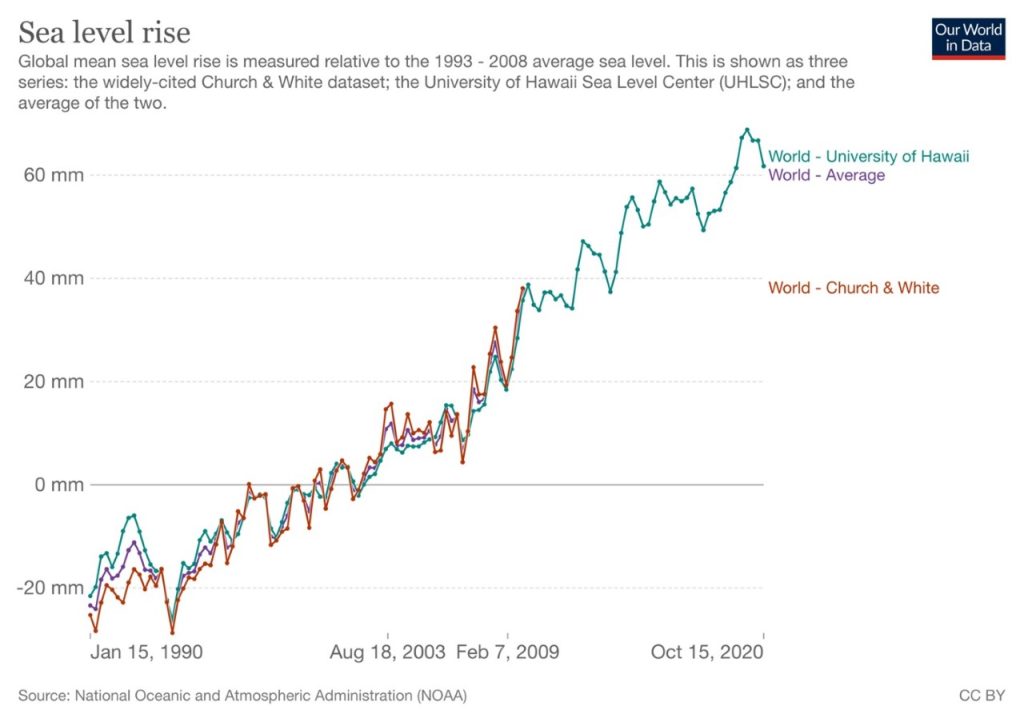

OurWorldInData.com

The last 30 years, the state of Florida, researchers and engineers have focused their enterprises on wind. Now they are addressing a new frontier in the battle against climate change: sea level rise.

A recent grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF) will give researchers at the WOW a new opportunity to test storm surge.

“There’s the wind is one of the weapons of the hurricane. The other weapon is storm surge,” Salna says. “So, if the hurricane makes landfall, it pushes that ocean water inland and that’s what floods and that’s why there’s evacuation zones.”

Strom surge plays a crucial role in a storm’s destruction.

Hurricane Andrews storm surge was recorded at 17 feet above sea level at Biscayne Bay.

Sea levels in Miami have risen a foot since the 1990s, nearly five of those inches came post-Andrew. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) also predicts sea levels could rise another six inches by 2030. And a new University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science-led study found that Miami Beach flood events have significantly increased over the last decade due to an acceleration of sea-level rise in South Florida.

Salna believes we must design differently to deal with worsened storm surge caused by rising sea levels. He points to new constructions that are being stilt-built in the Florida Keys.

Currently Miami-Dade County contains 26 percent of all U.S. homes at risk from rising seas, according to Zillow.

Salna says that new construction in South Florida would do “fairly well” to survive a Category 5 storm. “But a lot of the older stuff would not,” he says. “A lot of people would be displaced.”

Stakes are raised due to a growing population. In 1990, 1.937 million people called Miami-Dade County home. Thirty years later, 2.7 million people live within the county, an increase of 39 percent.

“The population shifted from the rust belt to the sun belt,” Salna says. A trend only exasperated by the Covid-19 pandemic, as Florida was the number one destination for people moving to.

Salna says that people living in coastal areas throughout the state need to have a realistic understanding of threats of severe storms and sea level rise. “You’re going to have to be ready and be prepared.”

A future above

With changes in population and sea levels continuing to rise, the time for FIU’s new testing facility could not be more critical. And while we do not know when the next major hurricane will strike Florida, we can better calculate the risk thanks to Hurricane Andrew and the funding that followed.

Creating infrastructure aimed to defy storm surge is the next step to creating a safer, more resilient Florida and one free of octopus-inhabited parking garages.