Guadalupe Alegre got her first job at 15 years old. She would rise early in the morning, just as the sun was starting to peek out from beneath the horizon, and make her way to Homestead’s fields. There she would spend the rest of the day bent under the scorching sun while tending the plants of a local nursery. Her hands were calloused and weary from the toil – and she would dream of holding a pen rather than a shovel.

That was impossible though. She knew her family needed the money.

“It was harder for me as the oldest of five siblings,” said Alegre. “I had to work to provide for them and help my dad. So, the fact that I could not attend high school was frustrating and depressing. A kid should be worrying about studying, not being a mom.”

Alegre was an undocumented immigrant. She arrived in the U.S. in 1998 and wouldn’t see the inside of a classroom until 2015, when she had two kids of her own and a husband to look after. Her plight reflects the harsh reality of millions of undocumented children who face all sorts of legal and practical barriers to access higher education.

Alegre was able to attend college after she applied for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals in 2012. DACA is a law passed by the Obama administration that granted more than 600,000 undocumented people the opportunity to attend higher education, work legally, and avoid deportation.

“It took a lot of effort for me to prove that I had been here since I was 15 so they could qualify me; immigration wouldn’t believe me,” she said. “I remember that it was only because I was able to find a receipt for some flowers I bought on Mother’s Day in 1998 that I could demonstrate my status.”

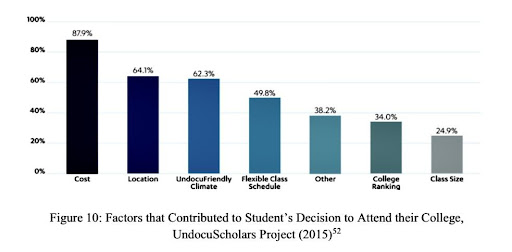

However, DACA only granted her the right to go to school. Due to her status, Alegre was barred from getting any type of financial aid or university scholarship. If she wanted a degree, she would have to pay for it out-of-pocket or win a private scholarship.

“I remember my husband told me I shouldn’t fantasize that much, that many people would probably apply to scholarships and that as I had never been in an American school, I probably wouldn’t get it,” she said. “I told him: ‘I don’t care.'”

In 2015, Alegre won a full-ride scholarship from TheDream.US program – America’s largest private fund for dreamers – and was able to attend Miami Dade College (MDC) that fall. She completed her associate’s degree in 2017 and transferred to FIU, where she graduated with a double major in accounting and business analytics in 2019.

“I suffered many humiliations as an agricultural worker,” she said. “Due to that, all I want for my family is a good education. Despite starting school so late, I am the first one in my family with an American diploma; that’s my pride. And I want the same for my children and siblings.”

Alegre’s story may be the last of its kind.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis is pushing a package of immigration measures that will impact the ability of undocumented students like Alegre to attend college or even exist in society. It is expected to pass within weeks because Republicans have supermajorities in both chambers,

Senate Bill 1718 is part of what DeSantis describes as a response to President Biden’s “open borders agenda.” It would make it a third-degree felony to “transport, conceal, harbor, or shield from detection” a person one “reasonably should know” is illegally in the country. In other words, anyone who gives a ride or houses an undocumented immigrant could be arrested and face up to five years in prison and/or a $10,000 fine.

Moreover, the bill will require hospitals to report to the governor any procedure they perform on undocumented immigrants. And it will authorize sheriff departments to take DNA samples of detainees. Finally, it will prohibit any municipality and non-profit from issuing driver’s license or ID to any who cannot prove legal status.

Overall, legal experts warn this would represent a de facto criminalization of undocumented people.

“SB 1718 would push thousands of people into the shadows,” wrote Elina Magaly Santana, a Miami-based immigration lawyer in a public newsletter about the bill. “The fear of being caught and reported will deter any undocumented persons from becoming productive members of the community. Do we all really want to become extensions of ICE in our everyday lives?”

According to the Migration Policy Institute and the Pew Research Center, between 772,000 to 825,000 undocumented migrants, around 4% of the population, reside in Florida.

“This should be the model for all 50 states going forward,” boasted state Sen. Blaise Ingoglia, a Republican from Central Florida who is the bill’s main sponsor. “We are not demonizing immigrants; we are demonizing illegal immigrants.”

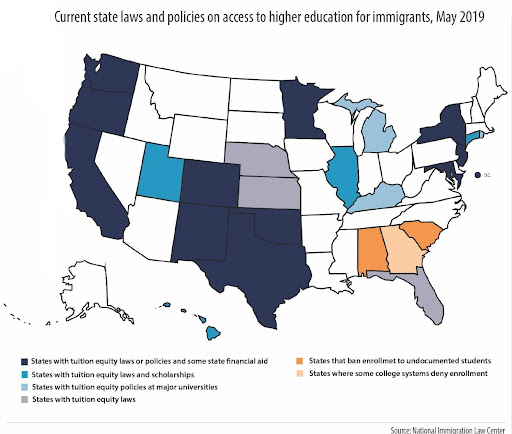

On top of these measures, DeSantis has also proposed overturning a 2014 Florida law that allowed undocumented students to be charged in-state tuition. In practice, this would mean that an undocumented full-time student at Florida international University who currently pays $6,757 a year would have to pay around $19,156.

“These students have no financial aid, they are not eligible for loans, and they have almost no income; all they have is our scholarship,” said Gabriela Pacheco, director of the Dream.US scholarship program and a former Dreamer herself. “Repealing something that has worked, that benefits us all, something that has allowed nurses, successful business owners, doctors, teachers, lawyers, and so many people to put incredible work in our state, makes no sense.”

Pacheco and dozens of Dream.US students from Florida have been traveling to Tallahassee every week recently to lobby legislators on a possible solution to the immigration package. They say it is not a matter of politics or ideology but basic human dignity.

“We have been sharing our stories, and the students have been the ones that have been leading this campaign,” said Pacheco. “Let’s be fair about this, right? Just give us equal access to education.”

If the larger immigration package is passed but the tuition increase fails, undocumented students would still be effectively barred from attending any university. That would make the institution complicit in a crime. But suppose the package fails in the legislature and the tuition change is implemented. In that case, students will be priced out of attending higher education and scholarships like TheDream.US will become almost useless.

“It’s both a catch-22 and a witch hunt,” said an FIU administrator who asked to remain unnamed to avoid reprisals from the state government. “We will either have to let students go because they cannot pay us or we will have to directly expel them to not commit a felony. Tallahassee’s message is clear: go north; you are not welcome here.”

However, despite this gloomy future, Alegre — who toiled in the Homestead fields – soldiers on. She is now an academic advisor, helping other students who, like her, didn’t have it easy in life. She is also trying to help her younger siblings get through college and invest in the education of her children and husband — who is now following his wife’s footsteps.

“My father always told me that all the inheritance he could give me was an education because he, even to this day with 72 years and a cancer diagnosis, still picks tomatoes in Homestead to provide his family with a better future,” said Alegre, sobbing. “Thus, all I can say to other students like me is don’t cry, keep your head up. You can do it… I did it.”

Aquiles Barreto worked on the video story. Steban Rondon authored the article.