Two years ago, Lester Estrada Cruz, a thin, strong, hard-gazing 30-year-old Cuban systems expert fled his home three hours from Havana after witnessing corruption and bribery by top government officials, then rebelling against his superiors.

Now he is in Miami seeking political asylum.

“In Cuba there is this thing called generalized theft, a dirty game that gives preferential access to electronics and basic resources to highly-ranked members of the government,” said Estrada. “The government is shaped by corruption from top to bottom.”

For more than nine years, Estrada worked as a network and systems technician at Empresa Electrica, the government-owned light and power company. He was in charge of fining people suspected of stealing electricity. After dealing with promises that were never kept and injustices by his superiors, Lester decided to leave. He spent months traveling through Central America riding buses, walking long distances, and nearly dying before he finally made it to Miami, where he has been awaiting a decision on his case for more than eight months.

Lester Estrada Cruz — Photo courtesy of Lester Estrada Cruz.

“The journey was tricky,” said Estrada. “On this trip nobody is safe, you never know what you will find or how it will go. Many times we had to sleep on the floor without food and under terrible conditions. Every night we dealt with the fear that something bad would happen to us while we were sleeping.”

Estrada comes from a small family that included a single mother, a younger sister, and a father who abandoned them to pursue his Communist ideals. His dad was a military officer who, he says, decided to support the government instead of his own family.

He is just one of the thousands of Cubans who have decided to leave behind everything and everyone they hold dear and start a new journey in search of happiness and equality.

Estrada’s situation has been massively complicated by President Barack Obama’s decision on January 12, 2017 to scrap a parole program called “wet foot, dry foot” that allowed Cubans to stay in the United States if they made it here. All they had to do was get a foot on dry land, and they were given residency. After the program ended, Cubans like Estrada were required to apply for status just like those from other countries.

This past September 30, things got worse when President Trump tightened the number of asylum claims for 2021. The administration announced that only 15,000 refugees would be admitted through the U.S Refugee Admission Program.

Maria Herrera Mellado, an immigration attorney at Kivaki Law Firm in Miami, said Trump has been defending his “America First” political program since his election by executing measures for greater control of national security. “His measures have been with the purpose of fighting back the rise of terrorism and organized crime gangs,” she said.

“It seems that president Trump’s administration does not read the history of the United States,” said Estrada. “This country is made by immigrants, and if we emigrate it’s because we are facing economic and political issues and not because we are terrorists.”

Estrada started his journey to the United States on June 6, 2019 by flying with a tourist visa from Cuba to Managua, Nicaragua. Once there, he bought a $30 bus ticket to Tegucigalpa.

In Honduras he found a coyote who was leading a group headed for the U.S-Mexico border. Soon they crossed Guatemala and entered Belize.

While Estrada was traveling from Belize toward the Mexican border, a girl in his group got lost in the jungle. “I don’t know what happened to her,” said Estrada. “Our crossing from Belize to Mexico was dangerous, since we had to ford rivers on horseback, and walk for hours without water or food.”

Estrada spent nine months living in Mexico applying for his humanitarian asylum. But he describes his experience in Mexico as a nightmare, not only because of the delays on his case but also due to crime .

His first stop was in Cancun, where he spent 23 days in a small house. Next, he and several others flew to Ciudad Juárez, a center of violence, drugs and organized crime activity just across the border from El Paso. On February 21, 2020 while Estrada was still in Juárez, a video of a furious gun battle between police and gunmen went viral on social media. This event left at least four people dead.

“A day in Mexico is a struggle,” said Estrada. “It’s normal to witness those kinds of violent events. It’s hard to live with fear, because you never know what will happen there are many things that the media don’t tell because they are also afraid of being killed.”

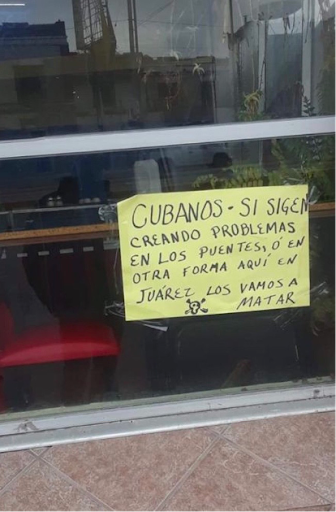

On the streets of Ciudad Juárez, he recalls seeing people being killed. “Where I used to live, the ‘mafia’ hung not only posters but also people,” he said anxiously. “They gave us the option to work for them or die. I refused, and I had to illegally cross the border because they could have killed me.”

A poster hung by the cartel in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. — Photo courtesy of Lester Estrada Cruz.

On July 8, 2019, he was caught by the U.S Border Patrol with a small group after entering the country. He said agents handcuffed group members and later asked if they were Brazilians. Then they took the group to a Customs and Border Protection facility.

After spending three days at the CBP facility, Estrada was released under the Migrants Protection Protocols program. During his stay at the facility, he faced horrible conditions including overcrowding, and cold temperatures.

“The conditions in the detention center were abysmal,” Estrada says.

They were forced to sleep in a frigid and cramped holding cell that prisoners called the freezer. The cell, he said, was extremely cold and more than 40 including kids slept on the floor.

“The agents at the CBP facilities are poorly trained to respond to the humanitarian crisis,” said Estrada. “We asked them to turn the air conditioning off, but they didn’t, and just they started laughing at us.”

During his second interview with the asylum officer, Estrada expressed fear that he might be harmed if he returned to Mexico. The court allowed him to stay in the United States while he awaits a final answer on his case. Since March 15, 2020, he has been living in a blue mobile home in Hialeah and working on the side as a handyman.

Estrada’s final court hearing is scheduled for December 10, but he fears it may be delayed due to COVID-19. Moreover, he could be sent back to the island because of new regulations the administration has implemented.

“If I return to the country where I was labeled as a traitor, it will be complicated because I won’t have any job opportunities and the government will make my life miserable,” said Estrada. “The tyrannical government always tries to find something dumb to use as a pretext to jail you.”