As Major League Baseball’s lockout threatens to delay the start of spring training and possibly even the regular season, an exhibit showcasing the history of America’s favorite pastime is front-and-center in the nation’s capital.

The Smithsonian Museum of American History’s “¡Pleibol! In the Barrios and the Big Leagues/En los barrios y las grandes ligas” explores Latinos’ key influences in the sport’s history and the “social and cultural force” it has in the Latino community.

Exhibit curator Margaret Salazar-Porzio spent six years preparing the exhibit. She traveled to Latino communities across the nation, speaking to community members and baseball experts and collecting information.

“Many communities showed up and talked about how baseball was an important way for them to express their identities and find their place in the world,” she said.

Two cities Salazar-Porzio visited, Miami and Tampa, contributed items and are prominently recognized at the exhibit.

Throughout the 20th century, surges of the Caribbean and South American migration to South Florida created a convergence between Latino culture and baseball. Close to 30 percent of major league players are Latino. They are from countries such as Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, Puerto Rico, and Venezuela.

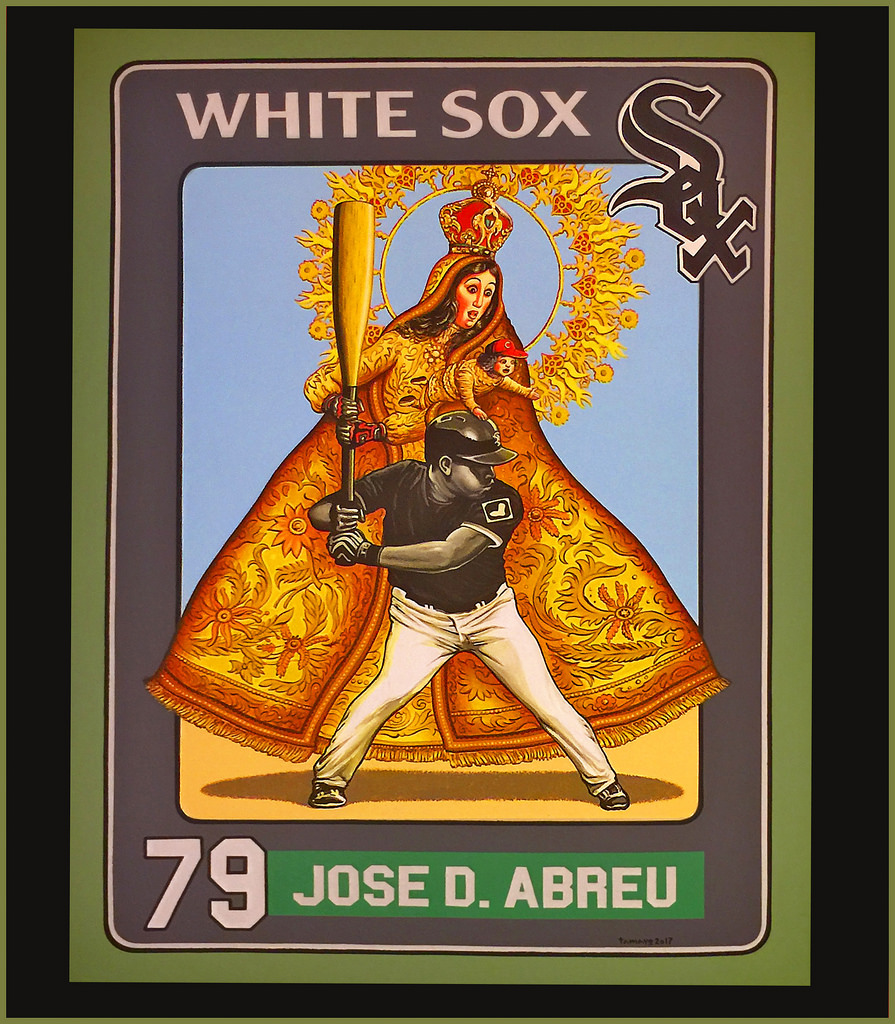

One of Salazar-Porzio’s favorite pieces, the “79 José D. Abreu” painting, depicts the Cuban baseball player preparing to swing a bat as Cuba’s patron saint, Virgen de la Caridad del Cobre, holds the bat behind him with a look of anticipation. The baby Jesus wearing a baseball cap reaches out to Abreu in the frame.

“It depicts how religion and immigration and baseball are intertwined in Cuba through the story of José Abreu, who had to leave his 2-year-old son at the time to play in the major leagues,” she said.

The painting was done by Cuban artist Reynerio Tamayo, whose work was on display as part of the Rodríguez Collection at the Kendall Art Center in Miami.

The Kendall Art Center facilitated the collaboration between the collection and the Smithsonian museum to donate the piece.

Collection owner Leonardo Rodríguez felt the painting best described the connection between Cuban culture and baseball and represented the exhibit’s message.

“It mimics a baseball card and has a Cuban baseball player with the Virgen de la Caridad and Jesus helping bat and step up to the plate, guiding him, and she is a staple figure in Cuban culture,” he said.

Abreu wrote about the experience in a letter to the Obama Administration in 2016.

“Apostles of the game.”

The exhibit names Cubans as the “apostles of the game,” spreading the sport across the Caribbean in the 1860s.

The early waves of immigration in the early 1800s saw the children of the Cuban elite, sent to study in the United States, returning to the island, spreading the knowledge of baseball to the rest of the Caribbean.

The sport soon spread like wildfire across the region, and in later decades, Cubans migrated to the Tampa region, bringing with them a knowledge of cigars and a love for the sport.

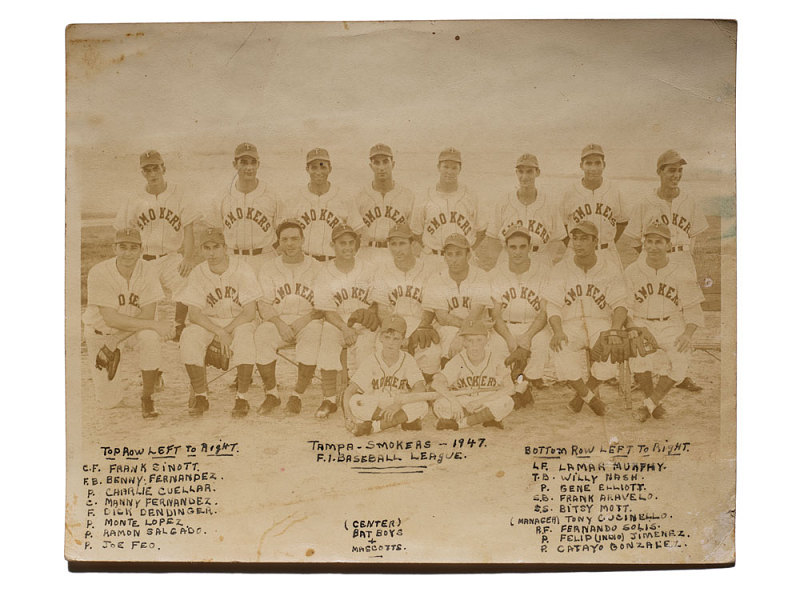

As a result, Tampa’s cigar industry boomed in the early 1900s, and the city was nicknamed the “Cigar Capital of the World” as it attracted thousands of Cuban families and workers from the island. The Tampa Smokers baseball team was formed in 1919, named after their blossoming cigar industry.

“As they were revolutionizing the cigar industry, they also changed the way baseball is played and the styles of the game, especially in South Florida,” Salazar-Porzio said.

The Cuban “fanatical baseball fans” and Latino residents turned out in large numbers to support the Tampa Smokers, the local minor league team.

Eventually, the team became widely successful and renowned in developing several Cubans who played in the major leagues.

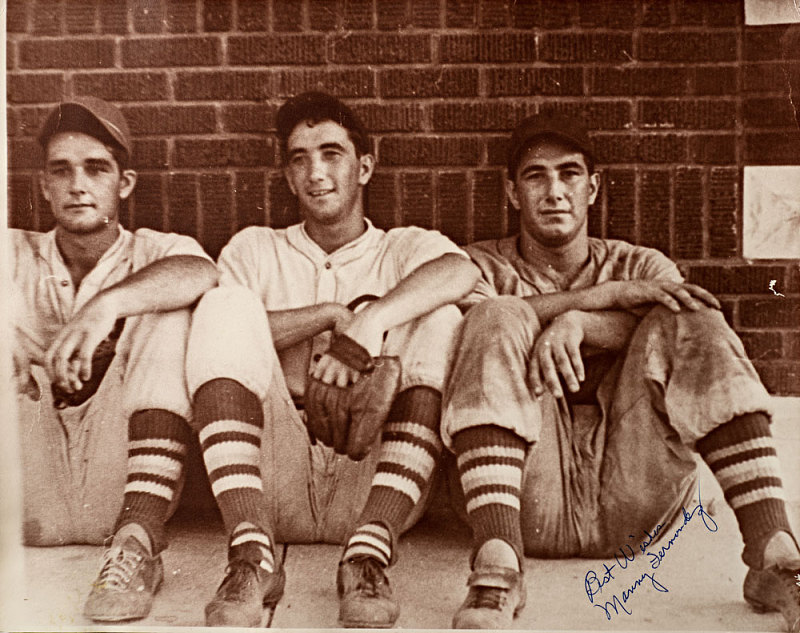

Salazar-Porzio recalls that one of the photographs donated from Tampa “opened the door to a whole lot of stories” about the Tampa Smokers and the community.

“That image opened the opportunity to talk about the team’s connection to the cigar industry and to talk about what brought people to the region and how baseball was integrated into different workforces,” she said.

The Pleibol exhibit also features a wide range of historical artifacts, artworks, and stories of influential Latinos in the sport. These figures include Roberto Clemente, the first Latino elected to the Hall of Fame, and Linda Alvarado, the MLB’s first female Hispanic team owner.

The exhibit comprises 145 new artifacts and the work of 1,000 participants in 17 collection events. The exhibition also tells ten oral histories relating to baseball and Latinos.

The exhibit opened on July 2, 2021, and is still on display at the Smithsonian Museum of American History. There is a traveling exhibit that will tour the country through 2025.

The exhibit can be viewed online.