Terrence Rountree walks along the Miami Beach Boardwalk every morning to bask in the view of the ocean and greenery, but even he admits that the city will never look as it once did.

“I cannot believe that so much damage has been done to this area that was so beautiful when I moved here,” said Rountree.

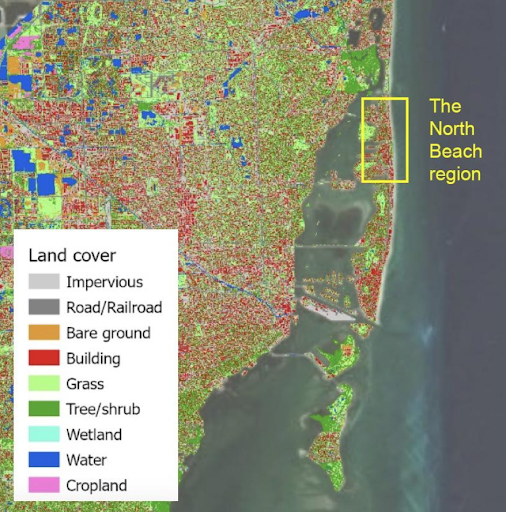

For almost 40 years, the North Beach resident has watched his neighborhood and the rest of Miami Beach turn into more concrete every day.

“I walk around the area often and I just think that the city has made terrible decisions,” he said.

Rountree says North Beach has undergone a subtle transformation. There used to be shaded areas along the beaches and pathways with a diversity of plant species that are native to South Florida.

In recent years, however, land development has spread throughout the coastal region, creating an unequal layout of urban versus green spaces.

But Rountree is not the only one who believes this.

The land-use problem is an ongoing battle between residents and the Miami Beach city council.

Often, this battle is chronicled by Nobe News – The North Beachian, a collective Facebook page for the northern Miami Beach area.

As the administrator for this platform, Ariana Hernandez-Reguant, an assistant research professor for Tulane University, advocates for both social and environmental injustice.

“In North Beach, only the gated communities like Stillwater, Biscayne Point, and Normandy Shores have received many trees to increase their canopy,” Hernandez commented. “The North Shore…is a tree desert and several degrees of temperature higher than its forested neighbors.”

Urban tree canopies (UTC) are vital not only for carbon sequestration in cities, but also for lowering the increased temperatures caused by climate change.

National Geographic author Alejandra Borunda explains how tree canopies help maintain cool temperatures in her article, “Los Angeles confronts its shady divide.“

“Direct solar radiation imparts more energy and therefore heat. Asphalt is a particularly good absorber, and along with concrete, it releases that captured heat into the air for hours, even after the sun disappears, contributing to the urban heat island effect,” wrote Borunda. “A well-placed tree, on the other hand, can keep a building 18 degrees cooler than if it were fully exposed to the sun.”

Miami-Dade County plans to combat the urban heat island effect with the Million Trees Miami Campaign, a community-wide program intended to reach a 30 percent UTC cover for the county.

Hernandez contends the county has made substantial efforts to implement tree canopies, mainly in high-income neighborhoods. In summer 2021, Miami-Dade partnered with the University of Florida and Florida International University to conduct an Urban Tree Canopy Assessment, specifically outlining this disparity.

The study showed that areas with a median household income of over 70k dollars per year have a greater percentage of shade from UTC.

The Urban Tree Canopy Assessment classifies the three municipalities with the largest percentage of UTC as Pinecrest (40%), Coral Gables (44%) and Cutler Bay (36.5%). According to the Miami Dade Matters organization, each of these neighborhoods are ranked as the 2nd, 6th and 18th wealthiest municipalities by median household income, respectively.

In contrast, Hialeah (7%), Medley (4%) and Opa-Locka (8%) have the smallest percentage of UTC. They are also ranked as the 61st, 63rd and 68th municipalities with the lowest median household income out of 69 neighborhoods in the county.

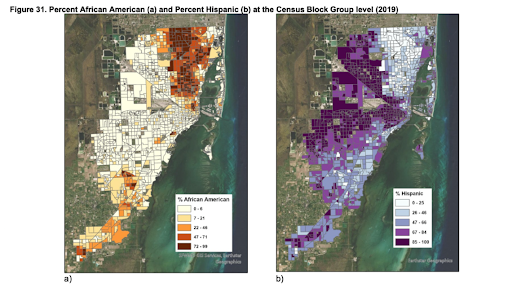

Additionally, the Urban Tree Canopy Assessment pinpoints the particular groups at a disadvantage due to low UTC. These are African-American and Hispanic residents of Miami-Dade County.

As a result of low UTC, low-income and minority neighborhoods experience higher temperatures and therefore, more public health concerns.

To compensate, some environmental organizations have stepped up to advocate for these vulnerable communities.

For example, Citizens for a Better South Florida (CBSF) is a multi-project organization providing environmental education opportunities to disadvantaged communities in Miami.

Their programs aim to help urban forestry and habitat restoration as climate change continues to be a looming threat to South Florida.

Although they have experienced recent funding cuts from Miami-Dade County, CBSF is hopeful that they will be able to continue their advocacy.

(Click below to listen to CBSF Program Director Marina Barrientos and Finance Coordinator Benjamin Machado discuss their urban forestry activism during the pandemic.)

During the pandemic, the non-profit has still accomplished several tree-planting projects. These few initiatives in minority communities remind them that their work is still valuable to residents, despite their limited funding from the local government.