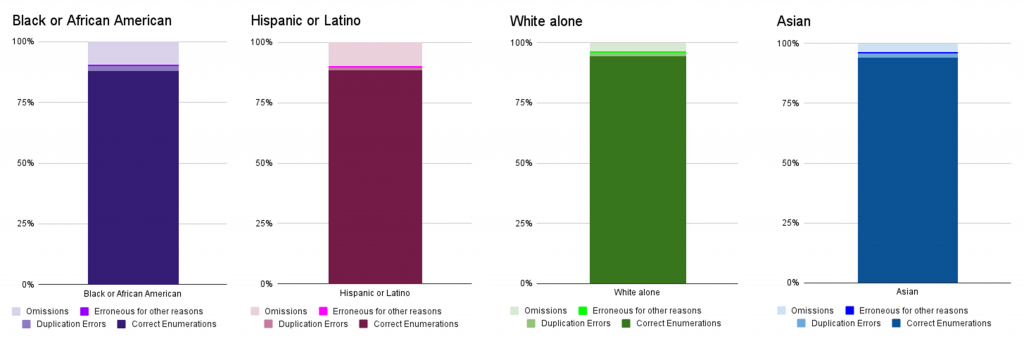

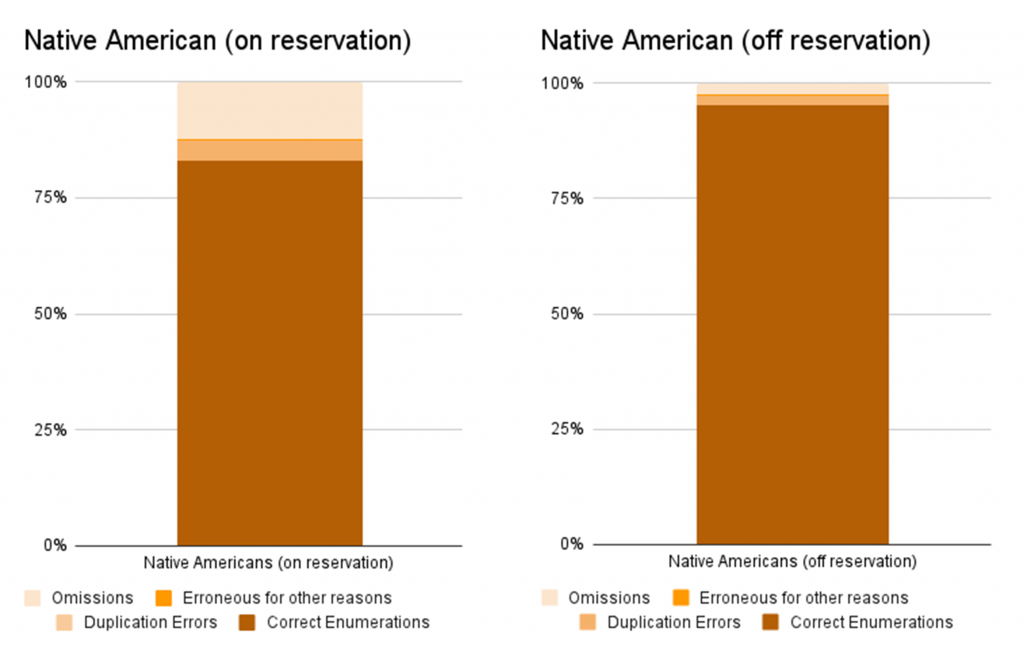

The U.S. Census Bureau recently announced it had overcounted non-Hispanic whites and Asians and undercounted Hispanic, Black, and Native American citizens during the 2020 census. This raised concerns from advocacy groups about inequity in funding and political representation.

The census results are used to fund billions of dollars a year for schools, road improvements, hospitals, and housing-related projects, among other issues. Populations of color tend to be those who need the most funding, and an inaccurate count means fewer dollars to those communities.

The National Urban League, a nonpartisan African American civil rights organization, commented that these results are not surprising considering the data collection process is fundamentally flawed.

“The Census Bureau must rethink and explore more accurate measures of the undercount and develop new data collection methodologies and operations for diverse populations,” said the National Urban League President and CEO Marc Morial in a statement. “Racial inequities are baked into the history of the Census process and the institution of the Census Bureau as an agency.”

The organization calls on the Bureau to find “equity-based” research to address the different causes of the undercount. They contend that systemic injustice in the census research and design has been “normalized” because of underrepresentation in the federal workforce that is tasked with the census. Minorities represent less than a third of the professional positions in the federal government.

Aside from equity concerns, the national level census figures are also used to determine congressional representation in the U.S. House of Representatives. Because the Bureau argues 2020 national results are accurate, there could be a reallocation of 435 seats in the House of Representatives, according to the American Statistical Association.

An undercount or miscount, however, could affect representation in districts where a majority of people of color live.

Census consultant Terri Ann Lowenthal explains that people who are more likely to be missed often don’t live in the same communities as those who are more likely to be counted twice, such as Non-Hispanic Whites and homeowners, in general.

“The communities that are overcounted get more than their fair share of political representation, government resources and private investments for the next decade while communities that were undercounted don’t receive what they need,” Lowenthal tells SFMN. “This accuracy gap and disproportionate counting of many of the same groups decade after decade results in such an inequitable outcome.”

Lowenthal adds that not all hope is lost for these communities to receive equal funding based on census numbers.

“Fortunately, the Census Bureau in between each census produces population estimates all the way down to the city level, and the town level. Those estimates are what’s used to allocate most government funding, not the actual census figures themselves,” she says.

The Bureau released data from two analyses known as the Post-Enumeration Survey (PES) and Demographic Analysis Estimates (DA), which are used to determine how accurately the census counted the national population.

They attributed inaccuracies to political interference from the former Trump administration and unforeseen circumstances such as the coronavirus pandemic, which derailed the Bureau’s data collection process.

Before reaching his position as Census Bureau director, Robert Santos informed Bloomberg CityLab, that he believed the Trump administration meddled in operations to benefit the Republican party before the election in 2020.

In an official statement from the Bureau, Santos recognized the challenges the agency has faced recently but asserted that the national data is still “fit for many uses in decision-making as well as painting a vivid portrait of our nation’s people.”

The PES data shows that the Census Bureau estimates 18.8 million people were omitted from the population. Lowenthal argues that while statistically accurate, the national count is not representative of the entire country.

“I define a successful census as one that counts all communities equally well, and yes the 2020 census regrettably did not do that,” says the census specialist. “I think the best thing that can be done is to look toward the next census and to find ways to modernize and update the census process so that it does count everyone accurately.”