Coral destruction is becoming an increasingly crucial concern for environmentalists.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, “Florida’s Coral Reef has been experiencing an outbreak of a coral disease termed Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease for over five years.”

This disease first appeared off the coast of Miami-Dade County in 2014.

Now, the growing epidemic has nearly engulfed the entire coral reef system in South Florida except for the Dry Tortugas near Key West, putting thousands of animal species, fish colonies and co-dependent ecosystems at risk.

This relatively new disease is a bacterial pathogen that spreads through contact or infected waterways. It can kill a coral reef ecosystem in weeks.

According to the United Nations Environment Programme, “Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease (SCTLD) is a rapidly spreading disease affecting over 20 species of hard corals in the Caribbean. These are some of the slowest-growing and longest-lived reef-building corals.”

SCTLD, along with other diseases, changes in water quality and temperature and invasive algae threaten the vitality of our coral reefs. The latent effects of coral destruction on South Florida can be potentially devastating.

“Healthy coral reefs can absorb 97% of wave energy from storms and hurricanes, buffering shorelines, and helping to protect people and property,” says the 2020 National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Coral Reef Status Report.

A study done by NOAA estimates that coral reefs in southeast Florida have an appraised value of $8.5 billion that includes thousands of jobs.

Letting this disease run rampant could cause losses amounting to billions of dollars in Florida and the Caribbean. Besides protecting against the destruction of property, flooding, erratic wave activity and erosion, coral reef systems also serve as biological ecosystems that house a great variety of wildlife.

Luckily, contemporary solutions are being worked on by NOAA through a collaborative effort titled Mission: Iconic Reefs.

“At its core, it is a 20-year-long phase approach to large-scale ecosystem-based coral restoration,” says Megan Fraser, NOAA’s Iconic Reefs Implementation Manager.

The initiative combats coral depletion by working with collaborative restoration practitioners at the local, federal, state, and non-governmental level.

MOTE Marine Laboratory, Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, the National Marine Sanctuary foundation, The Florida Aquarium, The Nature Conservancy, and various state universities are now working together with the organization to come up with solutions to save coral reefs.

“NOAA is the managing body and the leading authority, but it would not be remotely possible without having all of our partners working together,” says Fraser.

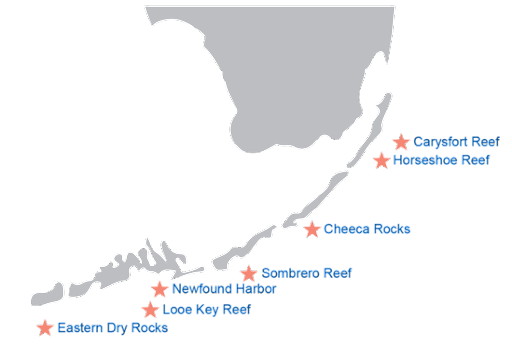

The mission focuses on seven major reef systems within the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary: carysfort reef, horseshoe reef, cheeca rocks, sombrero reef, newfound harbor reef, looe key reef, and Eastern Dry Rocks, which provide the organization with effective vantage points for restoration.

“There are sites in the Keys that have been known for generations by people and their families,” says Fraser.

“Historically, we are looking back and saying, ‘what were the iconic sites in the keys? what were the sites that people used to tell their kids and their grandkids about?’”

Iconic Reefs aims to restore coral reef ecosystems in the upper, middle, and lower Keys by allocating coral species to afflicted areas, monitoring growth, and ensuring coral reef longevity through habitat alignment.

By the end of phase two, NOAA and its collaborators hope to restore 25% of stony coral cover, partly by introducing fast-growing coral species like the elkhorn coral to stimulate coral growth.

They are also exploring the idea of introducing large amounts of Caribbean king crabs in afflicted areas to combat invasive algae.

Through micro-biology and genetics, MOTE scientists are working on introducing new genotypes to afflicted coral reef systems to create new generations of healthy coral.

By 2020, they succeeded in planting more than 100,000 coral species and have also restored depleted colonies through cultivation methods combining the use of land-based and underwater coral nurseries.

Through this approach, MOTE is also battling against the unprecedented reproductive failure that many foundational coral species are experiencing in the wild.

“To promote health and survival, especially in the face of environmental change and stress, we maintain genetic diversity within our restored coral populations through controlled and strategic breeding of native corals,” writes Dr. Erinn Muller on Mote’s Coral Reef Restoration webpage.