The United States’ gig economy is growing, with 57 million Americans now freelancing. “Gig-economy work is any kind of work that is performed under alternative work arrangements, meaning alternative to standard employee-employer relationship,” said Maria C. Figueroa, director of labor and policy research at the Worker Institute.

George Gonos, an adjunct professor at Florida International University, defined the economy as the result of people obtaining short-term jobs through online platforms. This can include professional work such as freelancing in journalism or delivering packages. It also can involve people who do temp-agency work, independent contractors, part-time workers and farm workers.

Digital platforms such as Uber, TaskRabbit and Freelancer.com make it easier for people to find freelance work. “Digitally mediated employment is the fastest growing segment of the gig economy,” said Figueroa.

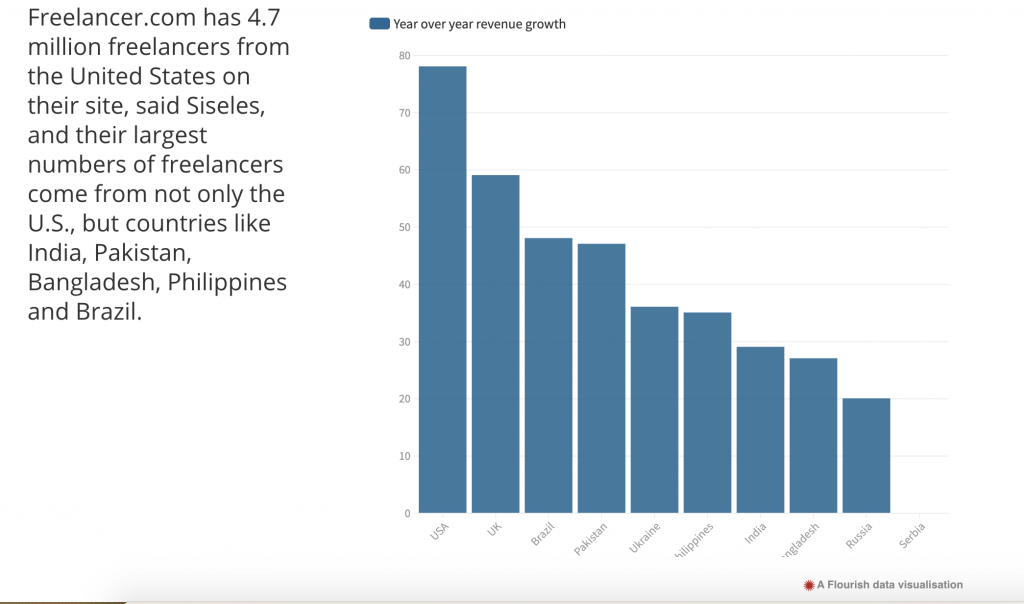

Freelancer.com serves 4.7 million freelancers from the United States and also includes workers from countries like India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, the Philippines and Brazil. “Any member can post a project or job and choose from freelancers to complete the work,” said Sebastián Siseles, Freelancer’s vice president of international expansion strategy.

Freelancer.com has a unique payment system, according to Siseles. Once an employer posts a project on the site and awards it, the chosen freelancer can request a milestone payment, which the employer can create by depositing funds. These funds are held by the website until the employer is satisfied and tells Freelancer.com to release the cash. “It’s probably the most secure payment system out there,” said Siseles. He said it’s better for a freelancer to work through the website rather than on their own.

The jobs most in demand on Freelancer.com are IT, design, marketing and communications, Siseles said. But there is a diverse group of freelancers on the site ranging from lawyers and accountants to geologists and programmers.

Offline, things are very different.

With the United States’ growing gig-economy, wage theft is becoming a problem. “Sometimes it would take up to four months after filing an assignment to see a paycheck from certain companies. Not getting paid on time takes a huge toll on your well-being and your finances. Imagine picking up a busy week of shifts at a restaurant and then they pay you half a year later for the labor you provided,” said Jinnie Lee, a former freelance editor.

“I am even still chasing down a few late payments right now. It can be frustrating, but unfortunately it’s something that you have to be prepared for as a freelancer since it’s pretty common to be chasing down late payments,” concurred Austen Tosone, a former freelance writer and editor.

“Many workers are vulnerable because they’re young, because they don’t have access to legal resources, because they’re an immigrant and are unaware of laws or threatened with arrest by customs and immigration,” said Gonos.

On top of stolen paychecks or late payments, workers often experience being labeled as independent contractors even when they’re doing the same work as a full-time employee. “Employers are labeling people independent contractors, they’re calling these things gigs, when they want to have all the power, but they don’t want the responsibilities that go along with it,” said Gonos.

Gonos also described adjunct professors, like himself, very often not having health insurance, not making a professional salary and not having professional “goodies” that full-time professors get, such as money to help further their careers.

Despite the lack of benefits, Gonos said colleges and universities are hiring more and more adjuncts to do their teaching. According to The American Interest, adjunct professors teach two-thirds of all classes in many colleges today. “Being an adjunct in the university arena is like being a poor farm worker,” he said. “You’re going from place to place and trying to piece together enough work to pay your bills.” Gonos also said that if students knew just how little their adjunct professors were being paid to teach a course they’d be shocked.

New York City’s Freelance Isn’t Free Act is the first U.S. law passed giving freelancers some protections. “Data has shown that freelancers experience wage theft at unacceptably high rates, when their hiring parties fail to pay what their contract requires,” said Melissa Barosy, press secretary for the New York City Department of Consumer Affairs. New York City’s 400,000 freelancers now have the right to a written contract and payment within 30 days absent a different, agreed-upon date.

“The Freelance Isn’t Free Act was a law created in New York to address the problem of companies taking advantage of freelancers and independent contractors,” said Andrew Gerber, one of the founding members of the KG Law Firm. He said companies sometimes decide not to pay freelancers because they know it’s often very expensive and intimidating for independent professionals to sue large companies to get the money they’re owed.

Gerber took on a case last year involving a well-known street artist named Eelco. He was hired by a restaurant to create a mural and after he completed it the restaurant refused to pay him. Eelco retained Gerber’s law firm and filed a lawsuit. The restaurant fought it for a year and its current attorneys have filed a motion to withdraw counsel because the restaurant was unable to pay them. The case is still pending, but Gerber hopes to get a judgment in Eelco’s favor.

“There must be thousands of aggrieved freelancers that have these problems on a daily basis and maybe aren’t aware that this law exists here in New York and aren’t aware that our firm handles [these types of cases],” said Gerber.

One resource available to freelancers in New York is the Freelancers Hub in Brooklyn. It provides free coworking, educational workshops, legal and financial clinics, benefits assistance and community events. The Hub is a partnership between the city and the Freelancers Union, a nonprofit that promotes advocacy for freelancers of all sorts.

There is new and pending legislation involving protections for freelancers in other parts of the United States as well. Barosy said New Jersey is currently considering a law similar to the Freelance Isn’t Free Act. Since more New Jersey residents are choosing to freelance with companies, state lawmakers are proposing labor regulations that will help make sure freelancers are treated fairly and are paid on time.

The California legislature recently adopted the AB5 Bill, which established the ABC test. “That test makes it harder for an employer to misclassify you as a freelancer or independent contractor when you’re actually an employee under the law,” said Figueroa. If the test shows that workers are actually employees, the employer has to pay the worker at least the minimum wage and provide them with benefits and insurance.

“California, New York and New Jersey are state leaders in labor and employment laws and policies,” said Figueroa. “I would say if they explore policies like these, other states may follow.” Although Figueroa thinks the Freelance Isn’t Free Act should have stronger enforcement mechanisms so that authorities are making sure that the law is being complied with, she also believes the act is a good model. “It would be great to increase the Freelance Isn’t Free Act from New York City to the entire state of New York,” she said.

In Florida, freelancers are treated as independent contractors and have some protections.

While Gonos believes states haven’t worked hard enough to legally protect gig workers, he is one of many people involved in these efforts. “I’m right now helping to write a kind of legislation that would protect temp-agency workers who are often badly exploited, making a lot less money for doing the same kind of work other people do,” he said.

For a more complete version of this story, visit http://gigeconomy.sfmnny.com/